|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| This weekly bulletin insert complements the curriculum published by the Department of Christian Education of the Orthodox Church in America. This and many other Christian Education resources are available at http://dce.oca.org. | |||

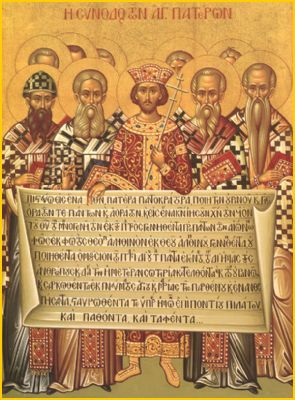

The Fathers of the First Ecumenical Council are commemorated each year on the seventh Sunday of Pascha. The gathering at which the fathers came together was held in Nicaea (present-day Iznik, Turkey) in the year 325. They were leaders of the Church, many of them bishops, and they were there in response to the summons of Emperor Constantine. He and they were concerned about a misguided theology that was gaining adherents and creating dissension among believers. Arius, a priest from Alexandria, was teaching that Jesus Christ was a created being rather than the divine Son of God, eternal and without beginning. Not every invited leader made it to the Council. It was spring, and the rivers in the east were flooded from heavy rains. There was always the threat of robbers on the roads, and many had to come long distances on those roads to reach Nicaea. But in spite of that, men came from many parts of the world: Carthage, France, Milan, Calabria, Spain, Cyprus, Armenia, Rome, Persia, Antioch, Constantinople, Alexandria and the Nile desert. One attendee was Theophilus the Goth, who had traveled from the largely unknown region of the North—somewhere in what is now Russia. Also present were men who would later become saints, including Nicholas of Myra and Athanasius of Alexandria. It was through their efforts, along with those of other participants who adhered to the Church's teaching, that the Council established what the Creed says about Jesus Christ: He is divine, and He is of the same essence as the Father. He is begotten of the Father, not made or created. The Emperor presided in splendid royal attire. But some of the men who attended were anything but splendid. Having come to Nicaea to deal with this new internal crisis of false teaching, they still bore the marks of the recent external crisis: the savage persecution of Christians by the state. One commentator has said that they were "the walking wounded, living demonstrations of how cruelly human beings can treat each other." The saintly Paphnutius, for example, hobbled along on legs whose sinews had been cut; he had only one eye, as did other victims of the emperor Diocletian and his torturers. Some men had skin that had been scorched by flames, or permanently scarred by the lashes of whips.

Yet here they were, still ready to serve Christ and the Church by laboring to create a statement that would tell the truth about the relationship of the Son to His Father. For Constantine, the important thing was to restore order and calm in the empire. His letter of invitation to the Council had read in part, "I entreat you that my endeavors may be brought to a prosperous end, and my people be persuaded to embrace peace and concord." But the "walking wounded" were defending a Kingdom, not some mere earthly empire. Whether with their blood or their words, they would not fail in that defense. |

|||