|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| This weekly bulletin insert complements the curriculum published by the Department of Christian Education of the Orthodox Church in America. This and many other Christian Education resources are available at http://dce.oca.org. | |||

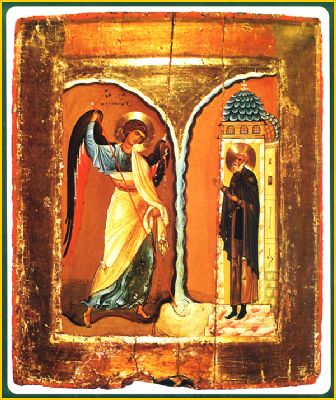

Mark 5:1-20 recounts one of the most dramatic of Jesus' healing miracles. The Church also remembers a very striking miracle performed by the Archangel Michael at Colossae. The story of the Archangel's miracle begins with the gratitude of a pagan father. This man's daughter, previously mute, was enabled to speak when she drank waters from a healing spring located near the city of Hierapolis. The father, desperate to find a cure for his daughter, had taken her to the spring after being told to do so by the Archangel Michael in a dream. Overwhelmed with thankfulness, the father and his family members were all baptized. Then the father oversaw the building of a church dedicated to the Archangel. As the miracle became widely known, people with illnesses and disabilities began coming to the spring for healing. Some were Christians, some were pagans and idol worshippers, and it made no difference. The spring's waters were effective for everyone. Many pagans who found healing at the spring followed the example of the mute girl's father, accepting baptism into the Christian faith. They were encouraged by the example of a believer named Archippus, who lived at the church and served as its sacristan for decades. His unassuming manner, combined with sincere faith, made Christianity attractive to people who met him. But some pagans feared the growing influence of the church that so strongly symbolized Christ's healing power, and decided to destroy it. They diverted a powerful mountain stream so that it would begin rushing toward the church and inundate it. Saint Michael intervened by opening a fissure in the mountain, so that the stream's water plunged into it, bypassing the church. Since that time the place of the miracle has been called "Chonae" which means "plunging." The account of the healing miracle in Mark's Gospel presents us with a man most people would hope to avoid. He lived "among the tombs" and was so violent that "he had often been bound with fetters and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the fetters he broke in pieces; and no one had the strength to subdue him." He was clearly miserable, for he "was always crying out, and bruising himself with stones." Such a man panics some people, and the only way they can think of to deal with him is with more and more chains. Jesus, by contrast, dealt with him calmly, fearlessly and lovingly. Instead of binding the man, Jesus freed him. He drove the demons out of him, and before long the people saw that he was "clothed and in his right mind."

The healing didn't make people happy; in fact they were "afraid" and asked Jesus to go away. Perhaps even something as terrible as demon possession had become familiar, and frightened them less than having to see God's love and power right before them in the Person of Christ. Might we, confronted with God in person, also hope He would just go away? |

|||