|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| This weekly bulletin insert complements the curriculum published by the Department of Christian Education of the Orthodox Church in America. This and many other Christian Education resources are available at http://dce.oca.org. | |||

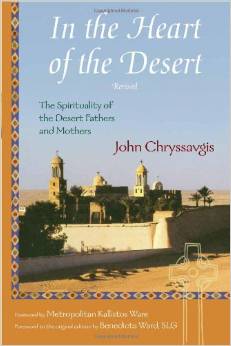

Christians from various backgrounds are discovering the writings of the early desert monastics, and are finding great spiritual profit in the examples their lives offer. A book entitled "In the Heart of the Desert: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers" by the Rev. Dr. John Chryssavgis (World Wisdom, Inc. 2003) gives insight into the lives of the desert-dwellers, and gently invites the reader to apply that insight in a personal way. The book also addresses some of the mistaken ideas that people may have about the monastic life. One important aspect of that life, for example, is dealing with the passions. These are understood, by many people, to be feelings and impulses that are completely negative. Monks and nuns are seen as those who spend their lives working to annihilate the passions. But Fr. Chryssavgis points out that while some monastics did seem to view the passions in this way, others saw them as neutral or positive impulses coming from God. Taking this view, Abba Isaiah of Scetis wrote about three passions: anger, jealousy and lust. We see them as evil, he says, because we have misdirected and misused them: "However, the original purpose of anger is for it to be used against injustice in the world; the proper reason for envy is so that we may seek to emulate the virtues of the saints; and the natural goal of our desire is to thirst for God." It is possible, Abba Isaiah and others say, first to identify our own personal passions—the things we desire or are strongly drawn to—and then redirect them so they become means of loving others and loving God. This is the long struggle the monastics undertook. They strove to become "dispassionate," which does not mean indifferent, but truly charitable toward the whole world. Fr. Chryssavgis uses Saint Anthony's example to address the common idea that monastics hated their bodies, and all matter. Anthony, after his intense fights with demons and extreme ascetical effort, was not emaciated or exhausted. He seemed to be in perfect balance, physically and in every other way. Anthony's very simple way of life seems extreme to us, Fr. Chryssavgis writes, only because "our culture teaches us that the more we have, the better we are; Anthony's taught him that the less he had, the more he was!" The truth is that "we can often manage with a lot less than we would dare to imagine." What did "obedience" mean to the desert monastics? Not submission to domination, Fr. Chyrssavgis tells us. Obedience was a circle, and "was expected of everyone, elders and novices alike!" True spiritual guides didn't seek to be idolized or to be absolute authorities. Mother Amma said that the teacher "ought to be a stranger to the desire for domination, vainglory and pride" and should be "full of concern for others, and a lover of souls." Beautiful illustrations enhance the richness of this book, which brings the reader closer to the early men and women of the desert who have so much to teach us. |

|||