|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| This weekly bulletin insert complements the curriculum published by the Department of Christian Education of the Orthodox Church in America. This and many other Christian Education resources are available at http://dce.oca.org. | |||

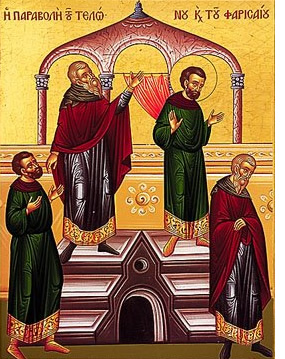

Part of growing up is being cautioned by our elders not to use "bad words." Avoiding vulgar speech is part of the reason for that caution. But as Christians we are also cautioned not to use our words to call down God's condemnation on other people. There is a patristic story that clearly shows the reason for that caution. We read that a young monk asks the elder, "Do the fathers always know their own powers?" "No," answers the elder, "they do not. Once, a brother became angry with another and said, 'I hope you may die and go to hell.' The other brother at once dropped down dead." The elder goes on with the story: "The brother who had wished evil on the other implored God to forgive his rash words. As he prayed, his brother monk came back to life. So this is the power of words for good and ill." Most of us needn't worry that our words could actually cause someone to die. Yet the story calls us to go beyond its literal details and to remember that our words do have power. We can brighten another person's day with a kind word or a cheerful greeting, just as we can cast a shadow with complaints or careless, indifferent words that do nothing to lift the spirit. A few encouraging words we hear as children can help us find satisfaction as adults; an unkind childhood nickname or a denigrating remark from a respected adult can wound us for years. The Publican and the Pharisee are two men whose words are significant enough to be recorded in Scripture. They teach us, among other things, that the number of words we say is far less important than the words we choose. The Pharisee talks on and on, using words with the facility of an educated and respected man. Yet the Canon of Saint Andrew dismisses his speech, saying that he "boasted and cried, 'O God, I thank thee', and then some foolish words." The publican, by contrast, whispers only a few humble words: "God, be merciful to me, a sinner." Yet it is this man and not the erudite one who, Our Lord tells us, will be saved. The publican's words are few but they have power because they acknowledge his sinfulness before God. They are steps on his path to salvation. Our society doesn't encourage us to value words for content rather than number. Seemingly forgotten is the example of Abraham Lincoln's address at Gettysburg, which delivered a stirring message in a few sentences. Long gone are the days when sending a telegram meant carefully counting the words to be sent because each one cost money. These days we are tempted with cell phone offers of "unlimited" calling—unlimited words we can send to others—and people spend hours texting each other. The 24-hour cable news channels are compelled to fill the airwaves with words describing events that, by any sensible definition, often do not qualify as news. The publican's words could be our silent prayer as we go through each day. It would be a spiritual help to us to ask God's mercy when we meet a new person. The words can remind us not to judge or make comparisons of ourselves with the person because he or she is also a sinner in need of God's mercy. When the day's events make us impatient, apprehensive, or annoyed, asking God's mercy can dispel our disturbing feelings, and help us take ourselves a little less seriously. The words of the publican can be for us, as for him, steps on the path to salvation. |

|||